Following the departure of the Nazi hierarchy first to the Wolf’s Lair in East Prussia – from where they would move onto their final destination in Berlin – the Kehlstein mountain was turned into a strategic observation post for the military. The installation of a number of anti-aircraft guns and the remote location itself would turn the house into something of a myth for the Allies, who until their arrival May 1945 believed the house to be the central hub of some secret Nazi alpine redoubt buried deep inside the mountain – the sort of myth that has since the war fuelled many a wartime comic-book fantasy.

Having survived the ferocious Allied bombing raid of 25th April 1945 which had flattened much of the Obersalzberg complex, both the Kehlsteinstraße and the mountaintop house remained intact until it was finally evacuated ahead of the rapid advance by American and French forces – with the first Allied units arriving in the Berchtesgaden area on 3rd May.

The first Allied unit to make its way up to the Kehlsteinhaus was led by Colonel Robert F. Sink, the commander of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. Among those who made their way up to the summit was Technician 5th Grade Ray Perry Eager, one of the many to be photographed in front of the “Mussolini” fireplace.

No fanatical SS Werwolf shock troops were lying in wait for the Americans, and perhaps the stiffest resistance Sink’s men encountered was the heavy falling of snow. Having made it to the summit, the Americans found both the entrance portal and the controls themselves completely blanketed.

The tunnel entrance was eventually cleared by POWs, but the first American troops to arrive had made their way to the house via the footpath, where they found everything just as it had been left by the previous occupiers. Every last fixture and fitting was still in place, but this would not last for long as numbers of nimble-fingered Allied troops would help themselves to the readily available collection of trinkets and souvenirs.

Some of the silver cutlery had been spirited away before the evacuation of the staff by house administrators Willi and Gretl Mitlstrasser, but anything that remained in the house that couldn’t be bolted down would eventually find a new home across the Atlantic. ![]()

![]() Did You Know?A small selection of distinctive 'Adolf Hitler' cutlery taken away from the Kehlsteinhaus by the Mitlstrassers would eventually turn up in the late 2000s, when they appeared at an auction in the United Kingdom.

Did You Know?A small selection of distinctive 'Adolf Hitler' cutlery taken away from the Kehlsteinhaus by the Mitlstrassers would eventually turn up in the late 2000s, when they appeared at an auction in the United Kingdom.

It would would take less than a week for the souvenir hunters to virtually clear the house of everything that was valuable or interesting, and by the time 101st Airborne commander General Maxwell D. Taylor ordered that the house be guarded, it was far too late. With most of the items have been removed, some of the more desperate souvenir hunters among the visiting GIs had even started to chip pieces away from the marble fireplace in the reception hall.

In the years immediately following the end of the war, there were some – including the many in the Bavarian State parliament – who suggested that the Kehlsteinhaus was little more than a Nazi relic, and that it should be destroyed. Common sense prevailed however, and thanks to the hard work of Karl Theodor Jacob, a local councillor and later the founder of the Berchtesgadener Landesstiftung (Berchtesgaden Foundation), the decision was made to open the the house to the public and promote it as a tourist attraction. The Kehlsteinstraße was repaired and reopened, along with a bus stop to the summit outside the Hotel zum Türken in Obersalzberg.

With the future of the Kehlsteinhaus assured, in 1952 it was leased for ten years to the Alpine Association – which in turn subleased the property to Josef Kellerbauer, who was responsible for the repair and renovation work – including the development of what would be the current restaurant.

The running of the bus route was the same time handed over to the local authorities, with a new bus terminal at the Hintereck being opened to be general public in 1960.

After the expiration of the Alpine Association lease the Kehlsteinhaus was then leased to the local Tourism Association, which renewed Kellerbauer’s lease of the restaurant. Kellerbauer was followed by Franz Sichert and then Herr Norbert Eder, who with his family runs the restaurant today. The house has undergone a number of renovations in the last fifty years, turning it from what was once a remote private retreat for a very small group of people into a popular tourist destination.

The Kehlsteinhaus Then and Now

While the repairs made to the house during the 1950s and 60s were extensive, there were no glaringly obvious additions to the existing building. The electrical system and lighting was replaced along with many of the original wooden doors and window frames, and a large outdoor terrace was added to the southern side to accommodate those guests who wanted to sip their coffee or beer while taking in a healthy dose of the fresh Alpine air.

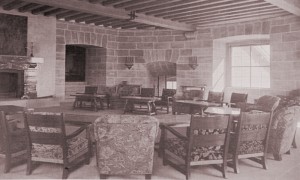

The table in the main dining room was removed and replaced by a number of smaller tables, while a number of other rooms were initially converted for use as dining areas for the restaurant including the octagonal main reception hall, Scharitzstube and guard room.

Perhaps the biggest change to the appearance of the building itself was on the southeast-facing sun terrace, where the large open arches were replaced by large windows. While this addition would change the general appearance of the building and negate the original “open plan” al fresco atmosphere intended by the architect, it meant that the terrace was longer affected by the climate outside – as well as reducing possible safety risks for the large number of visitors.

Further renovation work to what had become the main restaurant areas was carried out in the spring of 2010, with brand new flooring and furnishings being installed. The dining room was provided with a new modern-looking buffet and bar at its eastern end as well as new tables and benches, while the slightly tired furniture in the main reception hall was replaced with a selection of modern tables, chairs and benches with fresh-looking wood and glass.

In order to accommodate the installation of the new furniture in the dining room during this latest renovation, the large wooden china cupboard that had been positioned against the inner wall – one of the two remaining original items that had managed to survive the onslaught of the looters in 1945 – would sadly be removed. The removal of the china cupboard meant that the only one period feature remaining in the house was Mussolini’s marble fireplace in the main reception hall.

With the creation of more space in both the dining room and reception hall both the guard room and Scharitzstube are no longer used as dining areas, and the latter has been completely cleared of furniture to allow visitors the space to take in the unique atmosphere and the view of the mountains outside.

Exiting the sun terrace at the southern end takes the visitor to the new rear terrace which contains a number of outdoor tables, and from there the walk can be taken up the Mannlsteig path towards the summit, which is marked by the distinctive summit memorial cross or Gipfelkreuz, which was first erected in 1960. Probably the most famous view of the Kehlsteinhaus today is from the summit, where it can be seen sitting against the spectacular mountain-lined horizon.